Timeline

Title

Country/Nationality

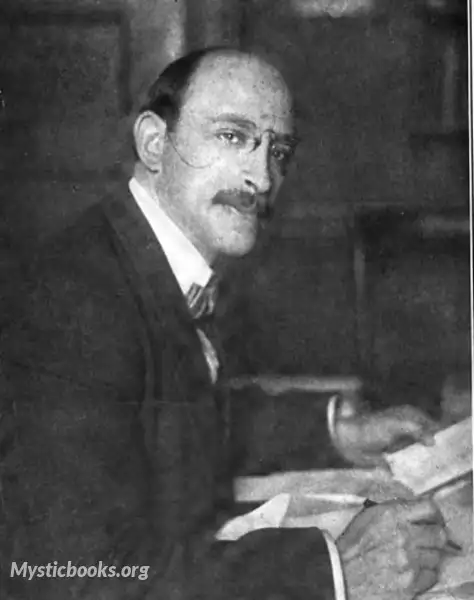

Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

Berkman was born in Vilna in the Russian Empire (present-day Vilnius, Lithuania) and immigrated to the United States in 1888. He lived in New York City, where he became involved in the anarchist movement. He was the one-time lover and lifelong friend of anarchist Emma Goldman. In 1892, undertaking an act of propaganda of the deed, Berkman made an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate businessman Henry Clay Frick during the Homestead strike, for which he served 14 years in prison. His experience in prison was the basis of his first book, Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist.

After his release from prison, Berkman served as editor of Goldman's anarchist journal, Mother Earth, and later established his own journal, The Blast. In 1917, Berkman and Goldman were sentenced to two years in jail for conspiracy against the newly instated draft. After their release from prison, they were arrested—along with hundreds of others—and deported to Russia. Initially supportive of that country's Bolshevik revolution, Berkman and Goldman soon became disillusioned, voicing their opposition to the Soviets' use of terror after seizing power and their repression of fellow revolutionaries. They left the Soviet Union in late 1921, and in 1925 Berkman published a book about his experiences, The Bolshevik Myth.

While living in France, Berkman continued his work in support of the anarchist movement, producing the classic exposition of anarchist principles, Now and After: The ABC of Communist Anarchism. Suffering from ill health, Berkman committed suicide in 1936.

Berkman was born Ovsei Osipovich Berkman in the Lithuanian city of Vilnius (then called Vilna, and part of the Vilna Governorate in the Russian Empire). He was the youngest of four children born into a well-off Lithuanian Jewish family. Berkman's father, Osip Berkman, was a successful leather merchant, and his mother, Yetta Berkman (née Natanson), came from a prosperous family.

In 1877, Osip Berkman was granted the right, as a successful businessman, to move from the Pale of Settlement to which Jews were generally restricted in the Russian Empire. The family moved to Saint Petersburg, a city previously off-limits to Jews. There, Ovsei adopted the more Russian name Alexander; he was known among family and friends as Sasha, a diminutive for Alexander. The Berkmans lived comfortably, with servants and a summer house. Berkman attended the gymnasium, where he received a classical education with the youth of Saint Petersburg's elite.

As a youth, Berkman was influenced by the growing radicalism that was spreading among workers in the Russian capital. A wave of political assassinations culminated in a bomb blast that killed Tsar Alexander II in 1881. While his parents worried—correctly, as it turned out—that the tsar's death might result in repression of the Jews and other minorities, Berkman became intrigued by the radical ideas of the day, including populism and nihilism. He became very upset when his favorite uncle, his mother's brother Mark Natanson, was sentenced to death for revolutionary activities.

Berkman spent his last years eking out a precarious living as an editor and translator. He and his companion, Emmy Eckstein, relocated frequently within Nice in search of smaller and less expensive quarters. Aronstam, who had changed his name to Modest Stein and attained success as an artist, became a benefactor, sending Berkman a monthly sum to help with expenses. In the 1930s his health began to deteriorate, and he underwent two unsuccessful operations for a prostate condition in early 1936. After the second surgery, he was bed-ridden for months. In constant pain, forced to rely on the financial help of friends and dependent on Eckstein's care, Berkman decided to commit suicide. In the early hours of June 28, 1936, unable to endure the physical pain of his ailment, Berkman tried to shoot himself in the heart with a handgun, but he failed to make a clean job of it. The bullet punctured a lung and his stomach and lodged in his spinal column, paralyzing him. Goldman rushed to Nice to be at his side. Berkman recognized her but was unable to speak. He sank into a coma in the afternoon, and died at 10 o'clock that night.

Goldman made funeral arrangements for Berkman. It had been his desire to be cremated and have his ashes buried in Waldheim Cemetery in Chicago, near the graves of the Haymarket defendants who had inspired him, but she could not afford the expense. Instead, Berkman was buried in a common grave in Cochez Cemetery in Nice.

Berkman died weeks before the start of the Spanish Revolution, modern history's clearest example of an anarcho-syndicalist revolution. In July 1937, Goldman wrote that seeing his principles in practice in Spain "would have rejuvenated and given him new strength, new hope. If only he had lived a little longer!"

Books by Alexander Berkman

Deportation: Its Meaning and Menace

A pamphlet written by Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman shortly before their deportation from the US in 1919.

The Bolshevik Myth

It explores the Russian Revolution and the rise of the Bolshevik Party in the early 20th century. Originally published in 1925, this book offers a firsthand account of Berkman's experience in Russia and his disillusionment with the Bolsheviks' leade...

Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist

Alexander Berkman's "Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist" offers a harrowing and insightful account of his experiences in the American prison system. The book details his 14-year sentence stemming from his involvement in a failed assassination attempt aga...

Mother Earth, Vol. 1 No. 4, June 1906

Mother Earth was an American anarchist journal that described itself as "A Monthly Magazine Devoted to Social Science and Literature". Founded in early 1906 and initially edited by Emma Goldman, an activist in the United States, it published articles...