Timeline

Title

Country/Nationality

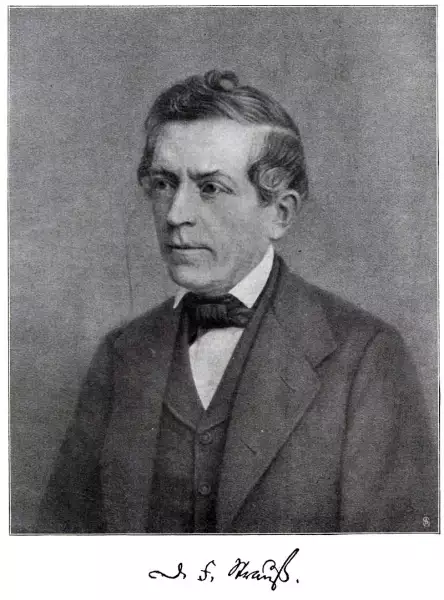

David Friedrich Strauss

David Friedrich Strauss was a German liberal Protestant theologian and writer, who influenced Christian Europe with his portrayal of the "historical Jesus", whose divine nature he denied. His work was connected to the Tübingen School, which revolutionized study of the New Testament, early Christianity, and ancient religions. Strauss was a pioneer in the historical investigation of Jesus.

Born and died in Ludwigsburg, near Stuttgart. At age 12 he was sent to the evangelical seminary at Blaubeuren, near Ulm, to be prepared for the study of theology. Two of the principal masters in the school were Professors Friedrich Heinrich Kern (1790–1842) and Ferdinand Christian Baur, who instilled in their pupils a deep appreciation for the ancient classics and the principles of textual criticism, which could be applied to texts in the sacred tradition as well as to classical ones.

In 1825, Strauss entered the University of Tübingen—the Tübinger Stift. The professors of philosophy there failed to interest him, but the theories of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Jakob Böhme, Friedrich Schleiermacher and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel successively claimed his allegiance. In 1830, he became an assistant to a country clergyman, and nine months later, he accepted the post of professor in the Evangelical Seminaries of Maulbronn and Blaubeuren, where he would teach Latin, history and Hebrew.

In October 1831, Strauss resigned his office to study under Schleiermacher and Hegel in Berlin. Hegel died just as he arrived, and though Strauss regularly attended Schleiermacher's lectures, it was only those on the life of Jesus that interested him. Strauss tried to find kindred spirits among the followers of Hegel but was not successful. While under the influence of Hegel's distinction between Vorstellung and Begriff, Strauss had already conceived the ideas found in his two principal theological works: Das Leben Jesu (Life of Jesus) and Christliche Glaubenslehre (Christian Dogma). Hegelians generally would not accept his conclusions. In 1832, Strauss returned to Tübingen, lecturing on logic, Plato, the history of philosophy and ethics with great success. However, in the fall of 1833, he resigned, to devote all his time to the completion of his Das Leben Jesu, published when he was 27 years old. The full original title of this work is Das Leben Jesu kritisch bearbeitet (Tübingen: 1835–1836), and it was translated from the fourth German edition into English by George Eliot (Marian Evans) (1819–1880) and published under the title The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined (3 vols., London, 1846).

Since the Hegelians in general rejected his Life of Jesus, Strauss defended his work in a booklet, Streitschriften zur Verteidigung meiner Schrift über das Leben Jesu und zur Charakteristik der gegenwärtigen Theologie (Tübingen: E. F. Osiander, 1837), which was finally translated into English by Marilyn Chapin Massey and published under the title In Defense of My 'Life of Jesus' Against the Hegelians (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1983). The famous scholar Bruno Bauer led the attack of the Hegelians on Strauss, and Bauer continued to attack Strauss in academic journals for years. When young Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche began criticizing Strauss, Bauer gave Nietzsche every support that he could afford. In the third edition (1839) of Das Leben Jesu, and in Zwei friedliche Blätter (Two Peaceful Letters), Strauss made important concessions to his critics, some of which he withdrew, however, in the fourth edition (1840) of Das Leben Jesu.

Books by David Friedrich Strauss

The Life of Jesus Critically Examined

Medical missionary Albert Schweitzer described Strauss' Life of Jesus as, "one of the most perfect things in the whole range of learned literature. In over fourteen hundred pages he has not a superfluous phrase; his analysis descends to the minutest...