The Genealogy of Morals

'The Genealogy of Morals' Summary

First Treatise: "'Good and Evil', 'Good and Bad'"

In the "First Treatise", Nietzsche demonstrates that the two pairs of opposites "good/evil" and "good/bad" have very different origins, and that the word "good" itself came to represent two opposed meanings. In the "good/bad" distinction of the aristocratic way of thinking, "good" is synonymous with nobility and everything which is powerful and life-asserting; in the "good/evil" distinction, which Nietzsche calls "slave morality", the meaning of "good" is made the antithesis of the original aristocratic "good", which itself is re-labelled "evil". This inversion of values develops out of the ressentiment felt by the weak towards the powerful.

Nietzsche rebukes the "English psychologists" for lacking historical sense. They seek to do moral genealogy by explaining altruism in terms of the utility of altruistic actions, which is subsequently forgotten as such actions become the norm. But the judgment "good", according to Nietzsche, originates not with the beneficiaries of altruistic actions. Rather, the good themselves (the powerful) coined the term "good". Further, Nietzsche sees it as psychologically absurd that altruism derives from a utility that is forgotten: if it is useful, what is the incentive to forget it? Such meaningless value-judgment gains currency by expectations repeatedly shaping the consciousness.

From the aristocratic mode of valuation, another mode of valuation branches off, which develops into its opposite: the priestly mode. Nietzsche proposes that longstanding confrontation between the priestly caste and the warrior caste fuels this splitting of meaning. The priests, and all those who feel disenfranchised and powerless in a lowly state of subjugation and physical impotence (e.g., slavery), develop a deep and venomous hatred for the powerful. Thus originates what Nietzsche calls the "slave revolt in morality", which, according to him, begins with Judaism (§7), for it is the bridge that led to the slave revolt, via Christian morality, of the alienated, oppressed masses of the Roman Empire (a dominant theme in The Antichrist, written the following year).

To the noble life, justice is immediate, real, and good, necessarily requiring enemies. In contrast, slave morality, which grew out of ressentiment, world-weariness, indignation and petty envy, holds that the weak are actually the meek (oppressed masses), wronged by those destined for destruction for their evils and worldly existence (the upper elite classes who thrive on the backs of the oppressed) and that because of the latter, the former (the meek) are deprived of the power to act with immediacy, that justice is a deferred event, an imagined revenge which will eventually win everlasting life for the weak and vanquish the strong. This imaginary "good" (the delusion of the weak) replaces the aristocratic "good" (determined by the strong), which in turn is rebranded "evil", to replace "bad", which to the noble meant "worthless" and "ill-born" (as in the Greek words κακος and δειλος).

In the First Treatise, Nietzsche introduces one of his most controversial images, the "blond beast". He had previously employed this expression to represent the lion, an image that is central to his philosophy and made its first appearance in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Beyond the metaphorical lion, Nietzsche expressively associates the "blond beast" with the Aryan race of Celts and Gaels which he states were all fair skinned and fair-haired and constituted the collective aristocracy of the time. Thus, he associates the "good, noble, pure, as originally a blond person in contrast to dark-skinned, dark-haired native inhabitants" (the embodiment of the "bad"). Here he introduces the concept of the original blond beasts as the "master race" which has lost its dominance over humanity but not necessarily, permanently. Though, at the same time, his examples of blond beasts include such peoples as the Japanese and Arabic nobilities of antiquity (§11), suggesting that being a blond beast has more to do with one's morality than one's race.

Nietzsche expressly insists it is a mistake to hold beasts of prey to be "evil", for their actions stem from their inherent strength, rather than any malicious intent. One should not blame them for their "thirst for enemies and resistances and triumphs" (§13). Similarly, it is a mistake to resent the strong for their actions, because, according to Nietzsche, there is no metaphysical subject. Only the weak need the illusion of the subject (or soul) to hold their actions together as a unity. But they have no right to make the bird of prey accountable for being a bird of prey.

Nietzsche concludes his First Treatise by hypothesizing a tremendous historical struggle between the Roman dualism of "good/bad" and that of the Judaic "good/evil", with the latter eventually achieving a victory for ressentiment, broken temporarily by the Renaissance, but then reasserted by the Reformation, and finally confirmed by the French Revolution when the "ressentiment instincts of the rabble" triumphed.

The First Treatise concludes with a brief section (§17) stating his own allegiance to the good/bad system of evaluation, followed by a note calling for further examination of the history of moral concepts and the hierarchy of values.

Book Details

Language

EnglishOriginal Language

GermanPublished In

1887Genre/Category

Tags/Keywords

Authors

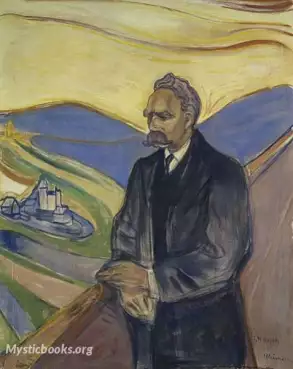

Friedrich Nietzsche

Germany

Nietzsche's writing spans philosophical polemics, poetry, cultural criticism, and fiction while displaying a fondness for aphorism and irony. Prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical c...

Books by Friedrich NietzscheDownload eBooks

Listen/Download Audiobook

- Select Speed

Related books

The Interior Castle by St. Teresa of Avila

The Interior Castle, or The Mansions, was written by Teresa of Ávila, the Spanish Carmelite nun and famed mystic, in 1577, as a guide for spiritual de...

Christian Mythology by Ethel Brigham Leatherbee

Ethel Brigham Leatherbee's "Christian Mythology" delves into the origins and development of Christian beliefs, arguing that Christianity, like other r...

Götzendämmerung by Friedrich Nietzsche

Diese kleine Schrift ist eine grosse Kriegserklärung; und was das Aushorchen von Götzen anbetrifft, so sind es dies Mal keine Zeitgötzen, sondern ewig...

Second Apology of Justin Martyr by Saint Justin Martyr

The Second Apology of Justin Martyr is a powerful and eloquent defense of the Christian faith written in the mid-second century AD. Justin Martyr, a p...

Temple: Its Ministry and Services As They Were at the Time of Jesus Christ by Alfred Edersheim

This book offers an in-depth exploration of the Temple in Jerusalem during the time of Jesus Christ. It delves into the physical structure, the intric...

Summa Contra Gentiles, First Book (On God) by Saint Thomas Aquinas

The Summa Contra Gentiles is a theological treatise written by Thomas Aquinas between 1259 and 1265. It is divided into four books, the first of which...

Bible (WEB) NT 01-27: The New Testament by World English Bible

The World English Bible is a translation of the Bible into modern English. Work on the project began in 1997, but the translation has been released di...

Fraternal Charity by Father Benoit Valuy

This book, originally written for members of religious orders, explores the virtue of fraternal charity. It delves into the fundamentals of this love,...

Bible (ASV) 05: Deuteronomy by American Standard Version

Deuteronomy, meaning 'second law' in Greek, is the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible and the culmination of the Torah or Pentateuch. Authored by Moses, i...

Laws by Plato (Πλάτων)

Laws is Plato's last and longest dialogue. It is generally agreed that Plato wrote this dialogue as an older man, having failed in his effort in Syrac...

Reviews for The Genealogy of Morals

No reviews posted or approved, yet...